Minister of the Interior of North Rhine-Westphalia Herbert Reul

on behalf of MIK NRW, Photo:

Jochen Tack

not only in Germany was the year 2020 marked by Corona – it also hit the people in Tanzania hard. It is all the more impressive that Dr. Fred Heimbach and his fellows have succeeded in completing numerous projects and moving others forward.

I would like to highlight one project of the past year: The completion of a new primary school in Emboreet. Now the children from the Emboreet area can finally attend a local school. Before, they often had to walk for hours and attended completely overcrowded classrooms. An untenable situation. Thanks to the willingness to donate and the support of a foundation, the project was accomplished and the children were given a new perspective.

The handicraft centre in the Simanjiro district is also being tirelessly expanded. Thanks to new workshop halls, not only more masonry apprentices but also carpenters and locksmiths can be trained as early as summer 2021. Boys and girls.

I am very excited to see what new projects await us in 2021 and look forward to being able to follow this valuable work.

Yours Herbert Reul

2020 – a Year marked by the Corona Pandemic

Meeting with a women’s group

The economic impact of the pandemic is severe for Tanzania. Tourism, the most important economic sector, has almost completely collapsed, and many people and their businesses have been left without any income. Without access to short-term unemployment benefits, unemployment insurance or a protective state umbrella, they were struggling to survive. Even though the borders were reopened for tourists in mid-2020, hardly any visitors came into the country, apart from the Eastern European tourists in Zanzibar.

After the end of the lockdown, in mid-2020 life returned to normal also for our partner organisation ECLAT Development Foundation. Meetings with the women’s groups in the villages were possible again after a relatively short lockdown, as were the courses for women at ECLAT’s seminar center. Our commitment to the expansion of the school infrastructure in the country was not affected by the pandemic at any time in 2020. The construction work on the primary schools and the continuation of the secondary school building measures in Emboreet went according to plan, as did the second phase of expansion of the Vocational Training Center which started in October. Carpenters and locksmiths are to be trained there as early as July 2021, in addition to apprentice bricklayers.

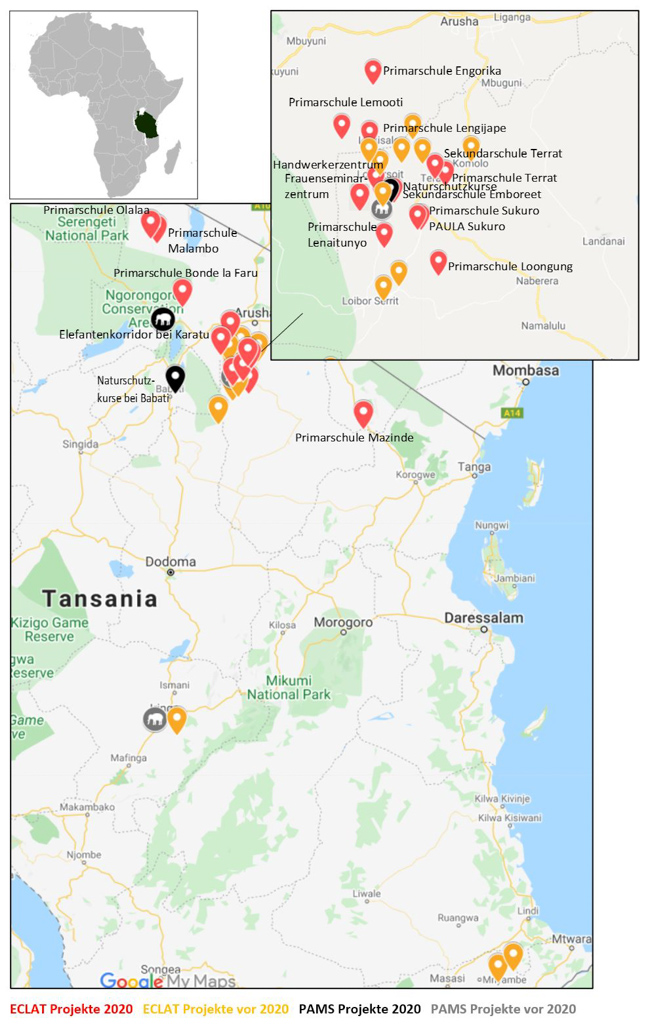

Where does upendo work?

New Construction and Expansion of Primary Schools

In the new classrooms of Lemooti Primary School

At the end of September, the new Lenaitunyo Primary School in Emboreet was handed over to the government. At the beginning of 2020, Chrismon magazine had reported in an article by photojournalist Claudio Verbano about the schoolgirl Pendo, who has to walk many hours every day from her home to school – and back again in the evening (see pages 6 to 7). Chrismon took the decision to build a new school near the home of this girl (and of many other children) as an occasion to appeal for donations. The resonance was so great that we were able to build significantly more buildings than initially planned. With the additional support of a foundation, five new classrooms, two residential houses for teachers (for whom there are no other housing options) and a new toilet facility were handed over at the end of September 2020. Then the students moved in. Pendo and many other children in the Emboreet area now have a reasonable school walk to their new school.

The rest of the schools in the area are grateful that many of their children can now receive education at another school, so that the number of children is significantly reduced in the classrooms – not to mention the fact that the number of children in a class is still far too high.

The Construction of the Secondary School in Emboreet is almost complete

Practical training in the biology laboratory of Emboreet Secondary School

Expansion of the Vocational Training Center

In the last months of the year, intensive construction work was done on the Vocational Training Center, especially on the new workshop blocks. These are also of central importance for vocational training and also in Tanzania they need to be adequately expanded and equipped. As early as July 2021, carpenters and locksmiths, boys and girls, are to be trained in addition to the existing bricklaying apprentices. Until recently, young people who could not qualify for an academic education at school had no chance of receiving vocational training in the district. But they now have the chance to learn something instead of seeking their luck in the big cities of the country or going back to their villages to herd cattle like their forefathers and to start families at a young age. They can settle in the district and contribute to the economic development of their communities. In parallel to the construction work and the purchase of tools and machines, the project also includes the preparation of the apprenticeship according to the German dual training model. The school will be run by VETA, the state authority responsible for manual training.

PENDO’S LONG WAY TO SCHOOL

Excerpt from the report: Long Walk Home by Claudio Verbano

Fog lies over the savannah landscape near the Tarangire National Park in Tanzania. It is 4 o’clock in the morning, two hours to go until sunrise. There is no sound to be heard in the small Massai settlement, inhabitants and animals are still in the middle of their sleep. Only in one of the huts something is stirring: The ten year old Pendo puts on her school uniform and starts her four hour long way to school…

Fog lies over the savannah landscape near the Tarangire National Park in Tanzania. It is 4 o’clock in the morning, two hours to go until sunrise. There is no sound to be heard in the small Massai settlement, inhabitants and animals are still in the middle of their sleep. Only in one of the huts something is stirring: The ten year old Pendo puts on her school uniform and starts her four hour long way to school…

It is pitch dark, the grass around the settlement is still damp from the fog. Pendo says goodbye to her mother Dahab, the only person who gets up with her so early. It remains a mystery how Pendo manages without an alarm clock, as not even a cock crows at this time of day. Her mother gives her some milk before she leaves the house. Pendo lives together with her mother, her little sister and her younger brother in a traditional Massai boma. Her way to school is long and arduous, altogether it is almost 20 kilometers to school and 20 kilometers back home, every day. On her way she walks alone for the first half hour, which is not without danger, since besides giraffes, zebras and buffalos there are hyenas and other animals that can cross her path at any time. Pendo is always happy to gradually meet other children. She runs towards school with quick and determined steps.

Pendo has been walking this route for four years now, she knows every stone, every tree and can therefore estimate exactly where she has to be when the sun rises to get to school on time. Those who are late are often heavily admonished by the teachers. Pendo urges the other children to hurry. But she can’t be considerate for long, because her goal is to reach school before eight o’clock, before morning roll call. When the sun rises at 6:30 a.m., it suddenly gets warmer. The sun is so strong that a short time later the fog disappears and a hot, dusty morning awakens from the cool night. Pendo is not impressed by this and leads her small group to school without a break.

Even though she is often tired at school,

Pendo always tries to participate well in class.

The young girl is often tired in the first lesson and sometimes falls asleep briefly. The effort she was able to ignore completely before is now getting to her. Her teachers are actually reluctant to tolerate this, but still let her rest a little. Everyone knows that she could be much better at school if she didn’t have to walk so many hours. At least Pendo obviously tries hard to follow the lessons, reports to the class and tries to do well, especially in geography lessons and Kiswahili, which is not easy with almost 50 children per class.

In every break Pendo tries to do her homework and repeat material from the lessons. She often asks other students for advice. In contrast to many others, Pendo does not have time after school to do anything else for school. Without electricity and light at home there is no possibility to read a book there. It is already dark when Pendo arrives home anyway.

For Pendo’s father Maiseyey it was always clear that his daughter should go to school one day: “I love our traditions, but as responsible parents it is also our duty to prepare our children for the future. School is a chance for us to learn how to stand up for our rights.”

It is often the challenges that make us stronger and more determined to fight for something. Pendo has long proven how much she fights for a school education.

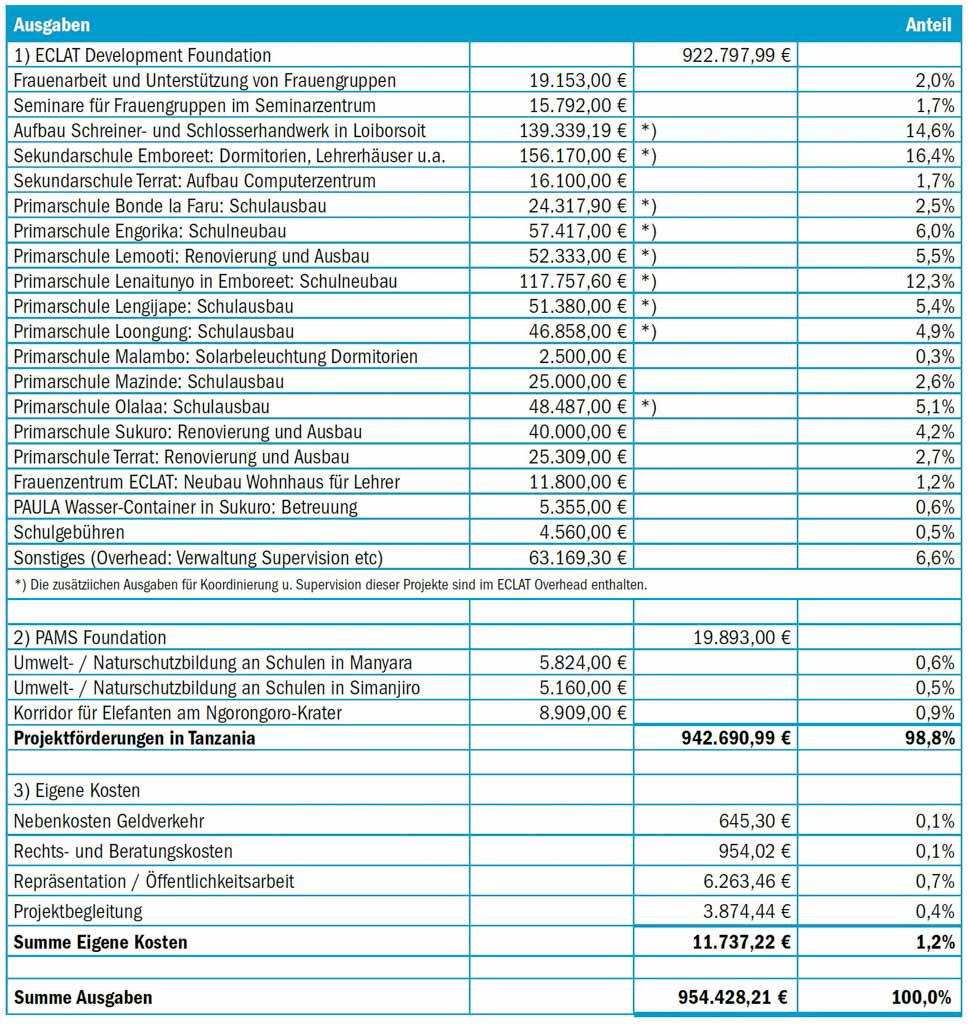

Mother Dahab puts her hand on her daughter’s

forehead – a typical Maasai greeting

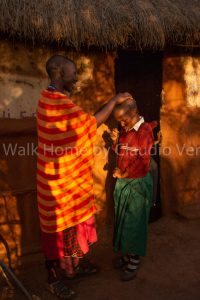

At home, Pendo shares a bed with her little

sister. In the future, they would like

to go to school together.

Photos: Claudio Verbano

ECLAT’s Women Empowerment

A group of women learns

to grow vegetables

ECLAT has been trying to strengthen the role of women in the Maasai culture for many years. Philomena Kiroya founded and leads this work. This includes the supervision of 75 women’s groups with a total of about 2,000 women in the villages of the district. The groups are visited by ECLAT staff in the villages to exchange experiences and to provide counselling in case of problems. Almost all of the groups have now received a micro-credit with which they can learn to manage their own businesses. Many of them find it difficult to all of a sudden have their own money and to manage it successfully. Some have economic success, others hardly any.

For more than three years, one of the women’s groups has been meeting weekly at the ECLAT Women Empowerment Seminar Centre to receive intensive training there from two teachers and to reflect together on the group and its success or failure. This is not an easy task when one considers that hardly any of the women have ever sat on a school bench to learn reading and arithmetic.

PAULA Water Filtration System

Clean potable water from

the PAULA plant in Sukuro

For already four years, the population in Sukuro has received hygienically clean drinking water, which is taken from the polluted and pathogen-contaminated reservoir and filtered through membranes in the PAULA container. In the meantime, the population has become accustomed to paying a small contribution to obtain clean water. And the water committee of the village has learned to run the plant reliably and to pay staff and buy spare parts and consumables with the money collected. ECLAT only needs to “look after things” from time to time or look for solutions to major technical problems. In cooperation with PAULA Water Ltd (GmbH), a second such plant is currently being built in the village of Narakauo.

Cooperation with PAMS in the Man – Nature Conflict Field

upendo supports the PAMS Foundation in environmental education in schools. The vision of PAMS is a world where wildlife and national parks are protected and people can live safely near them while understanding the value of nature. Since the park’s wild animals threaten the livelihoods of the neighbouring population and the parks’ grasslands are not available to the Maasai animal herds for grazing, the population is reluctant to share the idea of wildlife and nature conservation. The educational work at the secondary schools in the area of the Tarangire National Park has been expanded to about 10 secondary schools and now impacts about 2,000 children. The “club” is very popular, with a large proportion of pupils taking part in the voluntary events. They learn the meaning of nature and animal conservation, planting trees, and they visit the neighbouring national parks. In this way, they learn to understand the most important environmental problems of their region.We were also able to continue our project for the conservation of the elephant corridor at Ngorongoro Crater during the past year. The elephants in the crater migrate along centuries-old routes out of the crater to other national parks. However, due to the strong growth of the Tanzanian population, more and more people are looking for opportunities to cultivate more land. This easily leads to dangerous encounters with wild animals: Every year, many Tanzanians are killed in the ensuing encounters. But elephants also like to forage in fields that are ready for harvesting, so that people suffer from hunger. With a protection fence along the corridor, the elephants now stay in the corridor. The “fence” is made of cloths dipped in chilli broth. Elephants’ sense of smell is highly developed; the animals stay away from the fence and do not feed on the farmers’ fields or enter the villages. So the farmers learn to keep themselves and their fields safe and to live with the wild animals. It is only then that they are also willing to accept the idea of a national park and the existence of wild animals.

A road crosses the elephant corridor; a field in front.

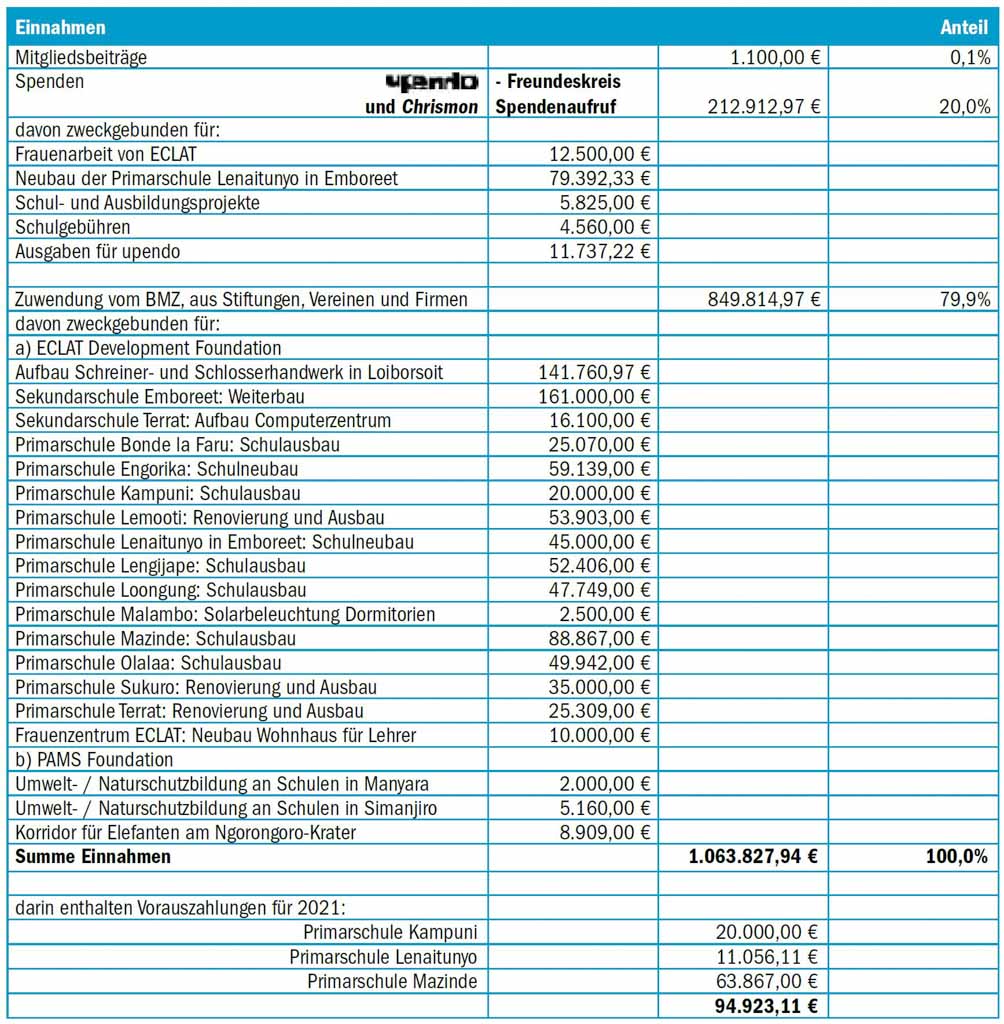

upendo Income in 2020

upendo thanks all those who support our work in whatever way they can, also on behalf of the communities that are affected in Tanzania. Special thanks for the support given pursuant to the 2020 treasurer’s report go to the Friendship Circle and the following organisations:

upendo Expenditure in 2020

upendo had the following expenses for the realisation of the projects in Tanzania according to the treasurer’s report 2020:

Transparency is a key issue for . Our annual treasury reports are subject to an external audit by the independent external tax consultancy JC Junga Consulting Ltd. in Solingen, Germany. The records on which the 2020 treasury report is based were also examined by this tax consulting firm and checked for compliance. In a letter dated 5 March 2021, the tax consultancy JC Junga Consulting Ltd. certified the accuracy of the treasury report for 2020, which has been published here on our website together with details of the treasury balance for the beginning and end of 2020 respectively.

WHO is upendo, HOW does it work and WHAT does upendo do?

upendo is an organization for the promotion of development cooperation at the municipal level in Africa, mainly in Tanzania. Project work is planned and implemented in close cooperation and coordination with representatives of the population and the government, which is ultimately responsible for the country and its people. The regular consultations at district and government level were also an important part of our work in 2020. Only locals work on project sites. In our two partner organisations ECLAT and PAMS, all project leaders are skilled locals who want to empower their people to escape poverty and backwardness and shape to shape themselves their own cultural progress. Well acquainted with the culture of their people they can initiate fundamental changes and impart these in such a way that they will be accepted. Founder of the association is Dr. Fred Heimbach. The Executive Board also includes Alexander Nikolakis and Joachim Buchmüller.

Founder of the association is Dr. Fred Heimbach. The Executive Board also includes Alexander Nikolakis and Joachim Buchmüller.

Contact: upendo – Registered Society to Support Development Projects in Africa, Am Rauenbusch 13, 42799 Leichlingen, Germany

E-mail: heimbach@upendo-entwicklungsprojekte.de

Photos: ECLAT, Rüdiger Fessel, Fred Heimbach, PAMS, Claudio Verbano

Tansania Stiftung

Tansania Stiftung