NRW Minister of the Interior Herbert Reul

on behalf of MIK NRW, Photo:

Jochen Tack

This newsletter focuses on the women’s work of our partner organization ECLAT: a work that can only be done by a Maasai woman who grew up in this culture and whom women trust.

Cultural backgorund

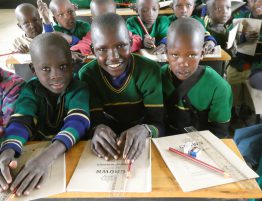

From a European perspective women have a difficult position in the culture of the Maasai. Traditionally, teenage girls are circumcised and forced into marriages. Women are not given their own property and they depend on their husbands economically and on all issues of their lives – men who are usually married to several women. Their role is to get many children, care for them and bring them up. In times of high infant mortality, this was a model that allowed the Maasai to exist with their families and their cattle in the conditions of the steppe of East Africa. Today, thanks to the vaccination programmes, most children survive. As a result, the population is increasing dramatically: the Maasai population doubles today in less than 18 years. Only one in four can read and write, far from all children go to school (we estimate only 3 out of 4), the number of early school leavers is high, in particular among girls, and schools are characterized by overcrowded classrooms, bad school infrastructure and too few, often poorly motivated teachers. But gradually the educational opportunities reach more and more Maasai. The number of children enrolled by their parents as new schoolchildren in recent years gives hope: it is increasing significantly, also among girls. Education is increasingly seen as a future investment for the children, which later benefits parents and the community as well.

Women’s work of ECLAT

Philomena Kiroya, head of the women’s work of our partner organization ECLAT and herself an educated Maasai, has set herself the task of improving the position of women in her society. She lives in her home village and at first has ensured that women formally join come together in groups, talk with each other and try to earn some money together. For Maasai women, who are normally allowed to leave their homestead (“boma”) only on special occasions, and whose possessions belong to their husbands, these are revolutionary changes. Within just a few years, these meetings have become a matter of course for the women. They have clearly become more self-confident and independent. And just as important: the men accept this development. Toima Kiroya, Philomena’s husband and leader of ECLAT, has a significant stake in this.

Women groups

Over the last few years, more than 100 women’s groups of 30 women each have joined forces in the district. It Iis impossible for ECLAT to manage all these groups and has therefore limited its activities to 75 official ECLAT women’s groups. At their regular meetings, the women of a group talk to each other about what’s on their minds. Philomena and / or her daughter Nosim sometimes take part in their meetings, often under a large tree in the village. We hope that all of these groups will have received a small starting capital by the end of this year. The women decide how they want to manage the money. Their business activities differ greatly: the operation of a corn mill, the production of bricks, the production and distribution of liquid soap, sewing works, breeding of cattle and the like. Some groups are very successful, others less so. The microcredit will be paid back to ECLAT over a few years and then benefit another women’s group. The women decide in their group on the use of the profit. One part is available to the women of the group; it can be used to benefit their children and families.

Seminary center

ECLAT’s seminar center for women’s work, which opened in October, is another big step: While the women usually meet in their villages for only a few hours, a group here meets for one week and is taught by two teachers. Most of the women have never sat at a school desk; it’s a strange experience to them. Here they learn about hygiene and health, how to deal with money, education and recently also on family planning. The women have realized that they barely managed to make ends meet for their many children, and many of them are now asking for help to limit the number of their children. Because the ethnic group of Maasai is currently threatened by backwardness, illiteracy and population growth in their existence: the steppe is overgrazed by their cattle, goats and sheep, the animals, on the other hand, are their livelihood.

The Uhuru Torch

The Uhuru (“Freedom”) Torch is an important symbol of Tanzania. Since independence, the Uhuru torch is carried annually in a run through the country. It shone for the first time in 1961 on the summit of Kilimanjaro and is still of great importance for the unity of the country. Traditionally, the torch is worn from place to place, and wherever there is something special to appreciate, it stops. For example, on June 16, 2018, this year’s Uhuru Torch Race also went to the primary school in Luagala (Mtwara region), which has just been renovated and expanded by us – a recognition and certainly also a little thank to the donors.

Fotos: (1) Rüdiger Fessel (2014), (2) Fred Heimbach (Mai 2018), (3) ECLAT (Juni 2018)